Why the Special Visual Effects of STAR WARS are so Special

May 4th, 2022

Matthew Teevan

I love the visual storytelling of the movies. I use the term ‘movies’ in the broadest sense of ‘filmmaking’ - whether it be movies, TV shows, live-action, animation, colour or black & white. The visual storytelling is so impactful. And for me, as it its most fascinating when is what is on screen can only exist on film. Animation and Visual Effects driven films and TV are a favourite.

I grew up in the 1970s and there was already a wealth of terrific visual effects work from movies and TV shows. The television programmes of Gerry Anderson, the films of Ray Harryhausen and George Pal and a handful of sci-fi movies from the 1950s and 1960s could all be seen frequently on TV.

In 1977 film making and visual effects changed with the release of ‘Star Wars’. It really cannot be overstated what an impact this film had. I was 10 years old when it was released; probably the perfect age and I was enthralled. People had never seen anything like it. It was fun, exciting and made with a level of craftsmanship and ingenuity that put a fantastic, but totally credible world on the screen like nothing before.

Anyone who saw that film in the theatre was struck with the opening shot. The impact of it, the level of realism and emotional engagement. Everyone was in awe. ‘That ship was huge’ was a phrase every schoolboy – and some dads – would utter.

But I am sure that some people who look at the movie now for the first time will see it is somewhat quaint. There are not hundreds of spaceships in every shot as there would be today. But what is there is classic in every sense of the word. The visual effects work in the film was a real turning point. Spectacular images had been put on the screen before, but ‘Star Wars’ not only raised the bar, but it also offered something new and fresh. It changed the audiences’ expectations. I want to talk about three behind the scenes things that made the special effects in ‘Star Wars’ so special.

Much has been discussed about the VFX and the impact of the Dykstraflex Motion Control system and this was a massive part of the visual effects accomplishment. And we will come to that.

But let’s start at the beginning with something that is often overlooked or taken for granted nowadays. In previous films the spaceships would either be flown via wires in front of a painted or backlit background. And the ‘flight’ is either puppeteered from above, or the ship is pulled along a track that is out of frame. This allows for smooth movement but is limited to motion in only one axis – forwards / backwards. Having a model small enough to be supported on invisible wires, was a factor too. Photographing the ship at a faster frame rate – such as 72frames per second vs the usual 24 fps - would also serve to smooth out the motion. The TV series ‘UFO’ has excellent examples of this technique with the UFOs and Interceptors in space.

Shado Interceptors fly in formation. All flown on wires in front of a painted backdrop and ‘moonscape’ set. All in camera, single pass.

UFO (1970)

An alien UFO approaches the Earth. UFO model flown on wires in front of a starfield backing and miniature planet. All in camera, single pass.

UFO (1970)

Another approach was to shoot the spaceship against a black backdrop. By having the model stationary and using a dolly (or similar set up) to move the camera toward or away from the ship would make it appear to be moving. Moving a large, heavy camera on a dolly or track system created smooth movement and having the model static means it could be supported via a sturdy pole, instead of delicate wires. The model could therefore be bigger and more detailed. The pure black background has no detail and with only the ship in the frame, there is nothing to give away that it is the camera and not the ship that is moving. However, to show stars or planets in the shot means that a separate exposure, or pass, to add in the planets is required. This was typically done ‘in-camera’, on the original negative with a single matte. This preserved image quality but limited as these elements could only be added to the portions of the frame outside of the path of the ship. Great care and creativity were needed to design the starfield in such a way so that the path the ship followed did not draw attention to itself as a ‘track’ or ‘path’ devoid of stars or planets. If the planets, or stars, overlapped the ship it would be double-exposed, making it look transparent, ruining the effect. This technique was used extensively to fly the Eagles in the TV series ‘Space:1999’.

An Eagle Transporter navigates a graveyard of derelict spaceships. Eagle shot separately from stationary derelict ships.

Space:1999 (1975)

A more elaborate technique was used on ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’, where again the ships were photographed against a black backdrop. Hand drawn travelling mattes of the spaceships were made that exactly matched the ship for each frame of film as it passed through the shot. This allowed the ships to pass in front of the stars. This was an extremely time-consuming process. An important factor with this process was that the image quality was preserved as the footage was combined as a first-generation print. More on this with the next technique.

The Discovery has ‘opened the pod bay doors’. The 54 foot long Discovery miniatures was photographed against black and a matte generated to combine it with the drifting starfield added as a second pass.

2001 :A Space Odyssey (1968)

Another common method was to shoot the model against a blue screen where again the ship’s motion in the shot was provided by the movement of the camera being pushed along on a dolly or some other track system. The ‘blue screen’ was akin to a cinema screen that was evenly lit with a specific shade of blue light that precisely corresponds to the blue film base. Great care is needed when lighting the model so that none of the blue light is cast onto the ship because the blue is ‘removed’ through a series of special printing steps to make mattes. These separate elements can then be combined with any other separately photographed element such as a star field or planets on an optical printer. An Optical Printer is a precision piece of equipment designed to photograph film prints (or negatives) with multiple exposures. The TV series ‘Star Trek’ used this technique to show the USS Enterprise flying through space. Having a library of shots of the enterprise against blue screen meant it was relatively straightforward and cost effect to change the planet element and make a new composite, without needing to reshoot the Enterprise for every shot!

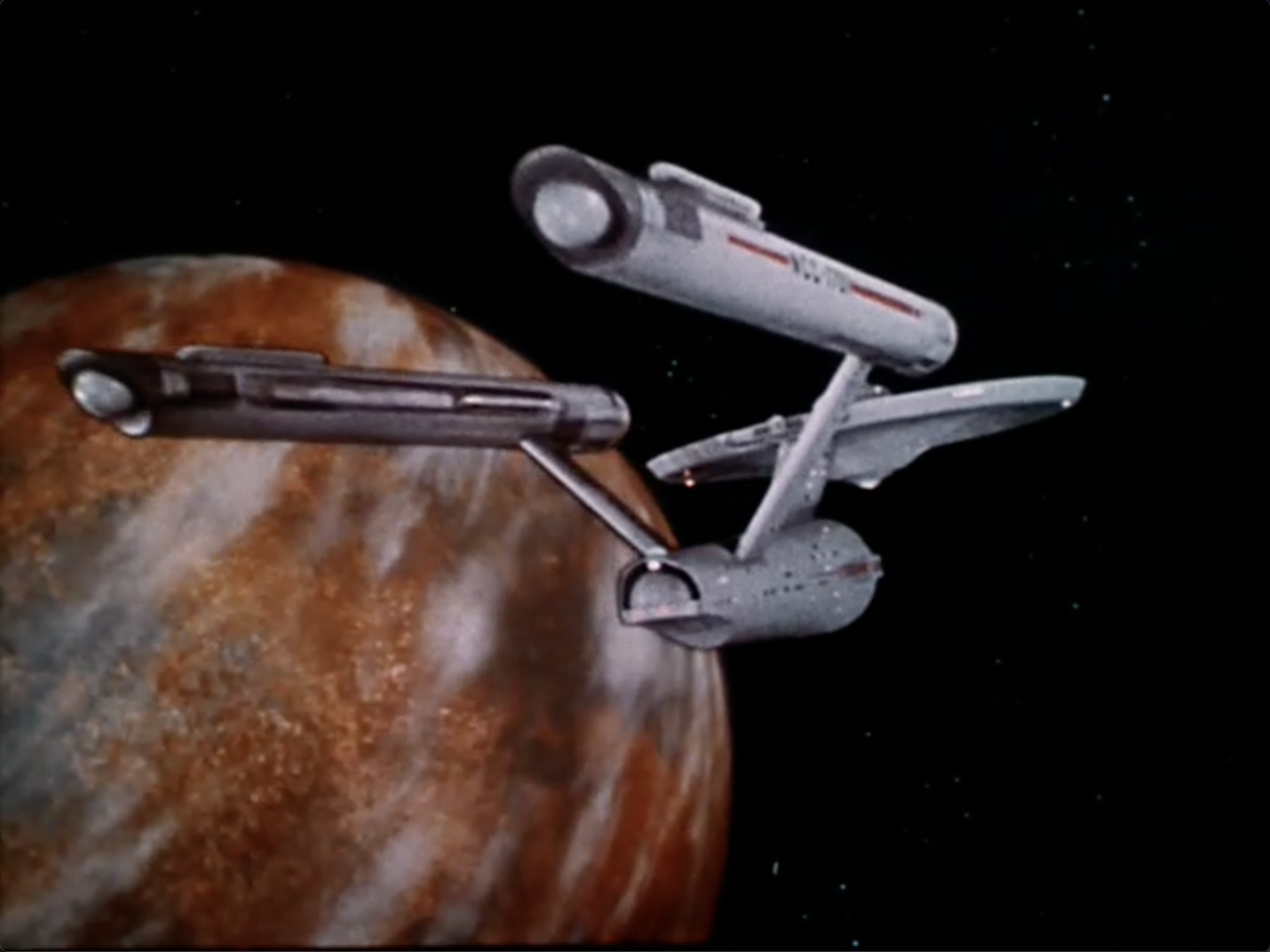

The USS Enterprise orbits an inhospitable planet.

The 14 foot long spaceship model was photographed against bluescreen and combined with starfield artwork and a rotating planet - each shot separately and combined on an Optical Printer.

Star Trek (1966)

The blue screen process was very complex and involved many time-consuming steps, each requiring extreme control at every step. Due to the nature of the various printing steps involved to get the necessary mattes, the film elements are several steps – or generations - away from the original negative. Every step involves re printing the existing film element onto a new piece of film. This added film grain on top of the existing film grain, and generally softened the image. This resulted in finished composite shots that looked grainier, were softer and sometimes showed different colour characteristics than the rest of the film. If you look at any old films from the 1950s or TV shows from the 1960s and every time where there is a shot that fades to black or cross dissolves with another shot, there is an abrupt change in the quality of the scene when the ‘optical’ is spliced in.

A common limitation when shooting multiple camera passes is that of matching the movement of the elements in the final shot. The speed of a truck-in or pan has to duplicated across all the passes, otherwise these will slide against one another in an unconvincing ‘scissoring’ manner. Any sort of shot with anything more than a rudimentary panning background was incredibly difficult and time consuming to achieve and involved a lot of trial and error.

So much of ‘Star Wars’ relied on the space shots and the credibility was critical to the success of the film. It needed to look as good, or better than any film before it. And the film would require more space shots than any film to date and these shots were more complex with fast moving ships chasing one another.

VISTAVISION

A key decision for Star Wars, and one that stayed with the visual effects community for decades since, was the decision to shoot the visual effects in ‘Vistavision’ format’. Vistavision was a system developed by Paramount Pictures in the 1950s as their entry in the competition to lure people away from their TVs and back into the cinemas with bigger, better-looking films. Cinerama kicked off this craze (creating a giant immersive movie experience via three cameras capturing 155 degrees of view). 20th Century Fox came up with Cinemascope, which used conventional 35mm film and special Anamorphic lenses to create a wider image. Following this came various 70mm systems, all requiring unique cameras and equipment. Vistavision used conventional 35mm but exposing a frame that is twice the image area of conventional 35mm movie film – which are 4 perforations high - making an image that was 8 perforations wide. It did this by running the film horizontally instead of vertically through the camera. The VistaVision images were literally twice the size of regular frames and as such there was more detail in the images.

Promotional material from Paramount Pictures in the 1950s showing VistaVision frame compared with standard 35mm frame.

In terms of visual effects work this meant that much cleaner mattes were possible. The inherent process of multiple prints and generations needed for blue screen work when using an 8 perf image resulted in final composites that ‘looked’ like an original 35mm image. The larger, superior image quality counteracted the multiple printing steps and inherent grain build up. The same things were happening, but the larger images were more ‘robust’. This is a broad statement but is basically true and ‘Star Wars’ does not have the tell-tale graininess in the visual effects shots. The optical composites in Star Wars were superior to what had come before.

‘Star Wars’ was shot in Panavision (an aspect ratio of 2.4:1) and Vista Vison was 1.66:1, so the final composites made on the optical printer were ‘letterboxed’ to 2.4:1) using an anamorphic lens and 35mm film which could be cut in with the original footage.

An Optical Printer circa 1975 - very similar to what was used on ‘Star Wars’. Two projector heads and a camea head (rhs).

MOTION CONTROL - (aka the Dykstraflex, named after Special Photographic Effects Supervisor John Dykstra).

Most often cited as the key to the success of the visual effects in ‘Star Wars’ is the development of the ‘Dykstraflex’ or ‘motion control’.

Motion Control is a system where a camera was connected to a series of specially engineered motors and gimbals to allow movement in all axes. This in turn was mounted to a track so that the camera could move forwards and backwards. The motors were all controlled via a computer, which recorded the camera movement, and enabled iterations and finesse of the same move. But the motion control system and had slow-moving mechanics in order to keep the movements accurate. This meant slower filming speeds but making the computer also control the camera’s aperture, long exposures were available. When photographing miniatures long exposures means less light is required and greater depth of field can be achieved. Typically, miniatures are photographed at high speed, and this means that more light is required and the inevitably the depth of field is decreased - with either the foreground and / or background objects having a soft focus, while the subject of the shot is kept in sharp focus. This is the ‘modelly’ look we have all seen in many films. The camera was continuing to move during these exposures too which meant the footage had all important motion blur. (It took several years for ‘real time’ motion control to be viable as an on-set tool for live action).

As the computer would store and playback the controls for the movement, or motion of the apparatus, the same camera moves could all be repeated for multiple passes on that same spaceship. For example, one pass for the ship and another pass for just the glowing engine exhausts. Shooting the exhausts separately – with all other lighting removed so that the exhaust was all that was being exposed. This meant that the internal lighting of the miniature could be dramatically over-exposed - and made much brighter than the internal illumination itself provided. This could even be shot with a filter to diffuse the light into more of a glow.

Visual Effects Cameraman Richard Edlund, reviews a Motion Control shot of the Millennium Falcon entering the Death Star hangar bay.

Graphic of the Dykstraflex. Camera head, hand held control input, camera on motorized axes, motorized trolley on track, computer.

Motion Control opened the door to shoot the same model in multiple positions and with suitably refined camera movement, providing ‘two ships for the price for one’. Having the ability to shoot almost anything separately and then optically composited allowed for a huge degree of control and therefore increased creativity.

Of course, shooting things separately and combining them with an Optical Printer was a very complicated process. The decision to shoot all visual effects elements in 8 perf ‘Vistavision’ made this viable. The bulk of the spaceship shots were shot against blue screen.

MINIATURES

The third things that was pivotal to the success of the shots was the miniature spaceships themselves. The design, or aesthetic of Star Wars was that of ‘used’ and in some cases pretty poorly cared for hardware. Ships were dirty, rusty in places, the bodywork shows temporary panels. The ships did not adhere to any needs for aerodynamics and were adorned with a lot of surface detail. The designs themselves look familiar – the X Wing Fighters sort of looked like jet fighters – and the lived in / used universe carried over into the models made them highly credible on screen. Familiar enough to have credibility, yet original enough to be exciting. A dedicated team of highly skilled model-makers was assembled. Hard to believe, but in the past a lot of spaceships for Hollywood movies were built by the studio prop dept. not model specialists! Much of the details came from plastic model kits – ‘kit bashed’ small detail parts from model tanks and battleships were scavenged and added to the spaceship hulls to provide a look of functionality. Kit bashing was first extensively on the TV Series ‘Thunderbirds’ and was used significantly on ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ and this film really established to cinema audiences what spaceships should look like.

ILM Modelmakers work on the 5-foot Millennium Falcon miniature

Close up view of the upper hull of the Millennium Falcon from ‘Star Wars’.

There is a fourth factor and that is the Director’s vision for kinetic space dogfights. Something that had never been seen before in a science fiction film. Spaceships were always grand and slow moving. In ‘Star Wars’ the story dealt with small single seater fighters. As the special effects took so long to create the Director used footage of actual WW2 dogfights which was cut into the reel temporarily to help pace out the shots and identify what was needed. In some cases, the motion of the spaceships matched the motion of the WW2 fighters exactly).

So, to sum up.

i) The models were extremely detailed and looked real.

ii) The ‘Dykstraflex’ motion control system enabled dynamic manoeuvrability for the spaceships and camerawork.

iii) Advances in Optical Photography and shooting elements on ‘8 perf’ eliminated the tell-tale graininess seen in previous films.

The opening shot is a perfect example of how all of this came together to deliver something never seen before. It is a terrific way to open the film and indeed it is one of the greatest shots in the history of cinema. Deep space. A spaceship races by. It is under fire from an off-screen pursuer. As the ship starts to disappear into the distance the pursuer enters the shot and starts to rumble overhead. It is enormous and it continues to pass overhead, revealing more and more of the gigantic vessel until the blinding light from the aft engines come into view. Phenomenal.

The first ship is actually a very detailed 6-foot-long model (which I believe actually cross dissolves (or cuts seamlessly behind a laser blast) to a separate take of a smaller scale model of the ship as it disappears into the distance). Both shot against blue screen.

The pursuing Star Destroyer that slowly fills the frame was a 3-foot-long model shot separately. The camera lens was mere millimetres from the hull of the model trucking back along it... virtually scraping the paint off the model! It looks enormous. The brightly lit engine exhausts were shot separately. The planets are matte paintings, the starfield is black cloth backlit with tiny holes creating the stars. Laser fire and flak was hand animated over frames of the two ships, from this backlit cel animation was shot separately. All of this was prepped for the optical work – the complex blue screen travelling matte process - and beautifully composited on an optical printer. The element all 8 perf being recorded onto 35mm anamorphic film. Add to this the terrific sound effects created by Ben Burtt and John Williams famous theme, and you have cinema gold. The result is a jaw dropping spectacle. As incredible as this shot is to watch, the behind the scenes of it is equally jaw dropping. Is that Star Destroyer really only 3 feet long? The level of detail and craftsmanship that the model makers put into the model is simply staggering. An incredible accomplishment.

A lot has been written about the special effects of ‘Star Wars’ with a view that this is where vfx really began. This is not true, as noted above films and TV had been utilising special effects and models for decades with some terrific results. ‘Star Wars’ started with those foundation building blocks and techniques and built upon those and added imaginative solutions to long standing problems. The level of creative control was unparalleled. The skill of the crew and the techniques employed set new standards, and this ushered in a golden age of science fiction and fantasy films and imaginative and ground-breaking visual effects.

This success of the film changed filmmaking forever. ‘Hollywood’ was willing to put unprecedented sums of money into Sci-Fi and Fantasy films. And there were filmmakers who were enthusiastic to meet and exceed the audience’s dreams with the new technology and creative freedom now available.

The next 10 years saw a wave of films that would strive to top the previous release. It was an incredible time for sci-fi and fantasy films and for the advancement and artistry of visual effects.

Some more of my favourite visual effects shots will be covered in upcoming blogs.

If you have any comments, questions or additional information, please email me at; matteline67@gmail.com

A frame from the opening shot of ‘STAR WARS’ (1977). Directed by George Lucas / Special Photographic Effects Supervisor John Dykstra

A link to a site that includes an excellent short video by MARK VARGO explaining the blue-screen process as used on ‘The Empire Strikes Back’.

https://nofilmschool.com/2016/07/watch-how-composite-blue-screen